Project Kpalimé (Pah-Lee-MAY)

Recent Updates

Baby Agoutis Are Here!!!

After one whole year, the moment we have been waiting for at the l’Envol in Kpalimé, Togo has finally arrived… As of the past two months, 14 new agoutis have been welcomed into the school’s sustainable farm!

Although they may not be the cutest babies you have ever seen, they will serve as the first generation of offspring that will be raised to breed and produce additional agoutis. Thus, the total number of agoutis at the farm is now at 23! Our hopes are to have upwards of 200 within the next two years, a goal that is completely feasible seeing that each female agoutis can give birth from 3-7 baby agoutis in a litter.

In other great news, the snail raising and mushroom cultivation programs implemented this summer are well on their way. Several batches of mushrooms have been cultivated for sale at the local market, as well as to local restaurants, and snails are expected to produce their first generation of offspring in the next 3 to 4 months.

With the addition of this past summer’s work, this is what Project Kpalimé has been able to accomplish over the course of the past two years:

$30,000 in seed funding ($15,000 from crowdfunding, $10,000 from Strauss Foundation, $5,000 from UCLA Global Citizens Fellowship)

Repairs to the director’s truck

Agoutis raising program

Snail raising program

Mushroom cultivation program

Crocodile pen

WiFi

Multiple months of feed for the school’s farm

New tools and equipment for the farmer and gardener on staff

Increase in children able to attend the school from 35 to 50

The addition of a farm employee

Official Facebook page

Individual meeting with the national director of Togo’s school’s for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities

And much, much more…

Don’t get me wrong, though – we have had countless numbers of roadblocks, mishaps, and hoops to jump through to get to this point. We were in a car crash, the government cut the Envol’s annual budget, several agoutis died, and so many other complications that you wouldn’t even begin to believe if I told you in person...

However, during this holiday season, it is important to be thankful for what we have, rather than what we do not. My time in Togo the past two summers has taught me many lessons, one of the most important being to always put things in perspective. Not matter how difficult life becomes, or how small we may think we are, life is always good; sometimes we forget.

Thank you for all you have done for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in West Africa.

Merry Christmas,

Grant

More Info

I. Introduction

My name is Grant Guess, and I am currently a sophomore at the University of California – Los Angeles. My older sister, Emily, suffered severe brain damage during birth that resulted in a number of intellectual and developmental disabilities. Emily requires assistance in almost all aspects of everyday life, from dressing herself in the morning to brushing her teeth at night. Having grown up with a sister with special needs, I have surrounded myself with individuals with disabilities for as long as I can remember. Whether it was in the form of coaching a Special Olympics basketball team, attending a summer camp for kids with intellectual and developmental disabilities, or interning at Special Olympics Southern California as a grant writer this past fall, the special needs community has continuously found its way into my life.

Even though Emily is limited to performing only a fraction of the activities people without special needs are able to perform, she still lives in a part of the world that widely accepts individuals with disabilities, both mental and physical. In West Africa, this is not the case. Children with disabilities are neglected, abused, and discriminated against on a daily basis; they are often left to sit inside their home all day to avoid public shame, are rarely enrolled in schools, and in extreme cases, are killed. In Togolese villages specifically, children with cerebral palsy who are unable to stand have been called “snakes” because they are forced to lie on the ground. A local non-profit representative in Togo stated, “To eliminate (kill) the child, ceremonies are organized at the river, where the child is left to drown and it is said that the snake is gone.[ii]”

After reading a research study released this past September by Plan International, a child development organization, describing the plight of children with disabilities in West Africa, I knew I needed to help make a change. Because of Plan’s article, my relationship with my older sister, and my past experience within the special needs community, I created a public service project in West Africa to empower children with special needs.

II. Plight of Children with Disabilities in West Africa

Widespread abuse, neglect, and discrimination of children with disabilities in West Africa have been well known for many years. However, the degree to which these children with disabilities have been mistreated has rarely been documented.

This changed in September of 2013 when representatives from Plan International publicized the situation of children with disabilities in West Africa in a research journal entitled, “Outside the Circle.” Plan’s research analyzed the attitudinal, environmental, and institutional barriers of children with disabilities through field studies in four different West African countries, including Togo. The journal confirmed the well-known but almost entirely undocumented mistreatment of children with disabilities in West Africa, exposing the role of people’s misperceptions of these children and, furthermore, uncovering the social stigma surrounding them. With this new data, researchers were able to examine how these children can potentially be better treated, accepted, and integrated into their respective societies. Plan International’s research concluded in calling to action governments, development agencies, and individuals alike to help change the way these children are perceived and to improve the overall livelihood of children with disabilities in West Africa and throughout the world.

An impairment is defined as a physical, intellectual, neurological, mental, or sensory characteristic that limits an individual’s personal or social functioning in comparison to someone without that characteristic; the limitation placed on an individual resulting from an impairment is a disability.[i] According to the World Bank’s 2011 Disability Study, it is estimated that 15% of any population has one or more impairments.[ii] Given that the population of Africa is over 1 billion people, of which 60% is believed to be under the age of twenty-four, we can deduce that over 90 million of Africa’s youth have an impairment leading to some form of disability.[ii] However, because of poor data collection, invalid census surveys, and shame among parents choosing not to register their child with a disability, the true number of children with disabilities in Africa is unknown.[ii]

Plan’s research in West Africa concluded that misperceptions and social stigma surrounding individuals with disabilities is multi-layered. Beliefs and assumptions are often based on cultural, religious, and historical beliefs of disability. In many villages, it is generally believed that physical and mental handicaps are the result of sins committed by the parents, an act of a sorcerer, or a punishment by God.[ii] Children with disabilities are discriminated against by their communities, families, or in many cases, both. The journal also uncovered that of all types of disabilities, children with severe intellectual disabilities or multiple disabilities are discriminated against the most.[ii]

III. Project Background

Project Kpalimé (Pah-Lee-MAY) is centered in one of Togo’s seven Medico-Psycho Pedagogic Institutes (Les Instituts Médico-Psycho-Pédagogiques l’Envol in French). The Consortium of Churches of Togo established these envols (as they are called for short) in the 1980s in an effort both to combat the false assumptions and stigma surrounding children with intellectual disabilities and to help them find a niche in their respective communities.[iii] The envols are the equivalent of specialized schools for children with special needs and are one of the only institutions providing educational programs and pre-professional training to children with special needs in Togo.

Since reading “Outside the Circle” and learning of the situation among children with disabilities in West Africa, I have been in contact with the director of an envol in Kpalimé, Togo, a small city just east of Togo’s border with Ghana, on a weekly basis. Mr. Théo Betevi, the envol’s director, has explained that many of the teenagers with special needs in Kpalimé are unable to attend the school due to budget cuts and limited spacing; instead, they spend their days either at home or wandering aimlessly around the village. Mr. Betevi has provided the plans for a project he believes will significantly improve the livelihood of numerous children with special needs in Kpalimé.

Mr. Betevi’s project involves building a sustainable grasscutter farm within the confines of the envol. Grasscutters (called “agoutis” in French) are small mammals similar to the groundhog that are widely hunted and eaten throughout Togo. They have been successfully domesticated, bred, and raised for sale in several West African countries. Grasscutter farms have proven to be extremely successful due to their minimal start-up cost, environment-friendly farming techniques, and long-term sustainability – with proper care and maintenance, the farms can be sustained for years to come. In addition, the small mammals are considered the easiest and most profitable livestock to sell due to their low mortality rate, inexpensive upkeep, and high demand among restaurants and markets, earning profits upwards of $30 US per grasscutter.[iv]

Mr. Betevi believes that establishing a program within the school to teach children how to breed and raise grasscutters to sell at the local market will “not only enhance the vocational opportunities available to teenagers with special needs through garnering them a sense of purpose,” but also “provide an additional form of subsistence to children with disabilities and add to the overall financial autonomy of the school.”

IV. Project Overview

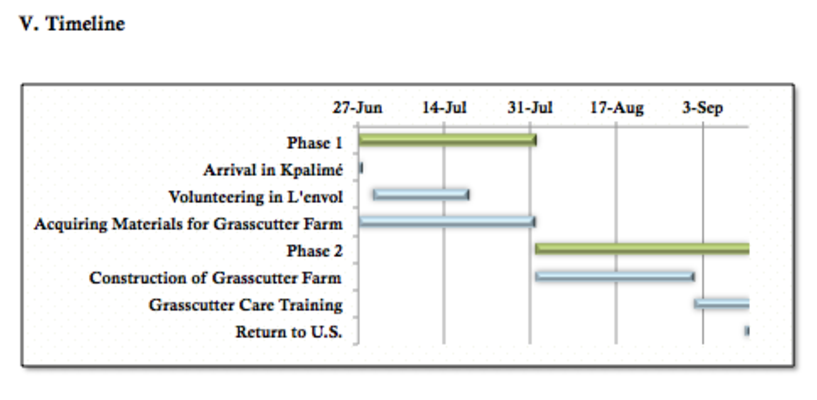

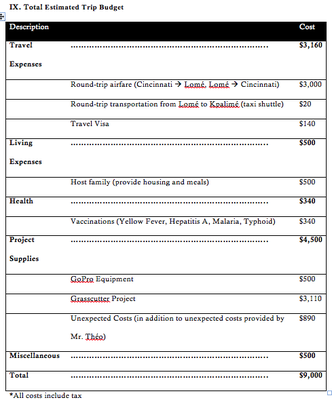

Project Kpalimé will be divided into three phases, beginning with my arrival in Kpalimé on June 27th, and continuing through my return back to the United States on September 12th.

Phase 1: Spanning from my arrival in Kpalime on June 27th, to beginning initial construction of the grasscutter farm on August 1st, Phase 1 will serve as an opportunity to build a relationship among the students and faculty of the envol. The school’s students are in session until July 18th, so I will spend the first two weeks of Phase 1 volunteering my time working with students and faculty to help me better understand the situation among children with disabilities in West Africa. Phase 1, as well as the subsequent duration of Project Kpalimé, will also provide an opportunity to improve upon my French fluency. In turn, this will allow me to further develop my relationships with students, faculty, and other community members, and to fully immerse myself within the culture. Additional time will be spent working closely with Mr. Betevi to acquire the materials necessary to begin construction of the grasscutter farm, scheduled to commence on August 1st.

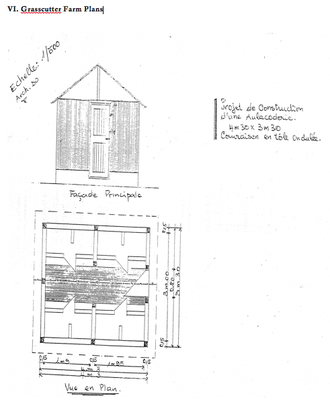

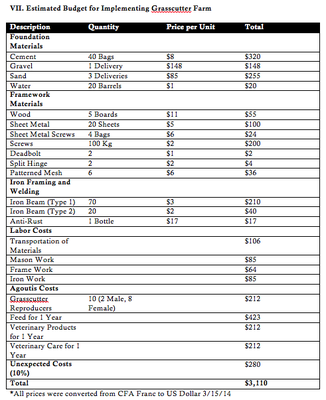

Phase 2: The second phase of Project Kpalimé will be devoted to the construction and implementation of the grasscutter farm, beginning with initial construction of the farm on August 1st and concluding with my departure on September 12th. Following construction of the actual pen which will house the grasscutters (see Section “VII.” below), the implementation sub-phase will begin. This sub-phase will entail working with the gardener and farmer on staff who will be training the school’s special needs children with the skills necessary to breed and care for the grasscutters throughout the years to come.

Phase 3: The final phase of Project Kpalimé encompasses everything to occur from my September 12th departure onward. The goal of Phase 3 is to raise awareness of the abuse, neglect, and discrimination of children with disabilities in West Africa through the promotion of Project Kpalimé upon my return to UCLA in the fall. In order to do this, I plan to make a promotional video with the help of a personal friend employed at a video editing company in Los Angeles using footage from the project recorded on a GoPro© high-definition personal camera. This promotional video will serve as the focal point of a social media marketing campaign that will allow me to market and promote Project Kpalimé and other future humanitarian endeavors aiding children with disabilities in West Africa.

V. Possible Humanitarian Endeavors as a Result of Project Kpalimé

If Project Kpalimé is a success, it has the opportunity to involve other humanitarian organizations to aid children with special needs in West Africa. One of those organizations is Best Buddies International, a non-profit organization devoted to creating opportunities for one-to-one friendships, integrated employment, and leadership development for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Best Buddies International has instituted programs in over fifty countries, but has yet to establish a program in Togo.[v] Diana Rihl, Deputy Director of International Programs, and other members of the international programs staff, have expressed interest in working with me upon my return to evaluate possible methods to implement programs in Togo. As a result, Project Kpalimé will also serve as an opportunity for me to gauge the effectiveness of a program like Best Buddies in a single Togolese city, as well as if it could possibly develop and expand into other cities and schools across the country.

Another possibility involves Rotary International, an international service organization that brings together business and community leaders across the world to provide humanitarian services. Mr. Betevi, the director of the school for children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Kpalimé, is also the president of the city’s Rotary Club. I am currently working with Mr. Betevi in connection with other Rotary Clubs to see how Kpalimé could possibly be aided in other aspects in the near future.

VI. Conclusion

Although the implementation of a grasscutter farm at the envol in Kpalimé will not directly solve the social stigma surrounding children with disabilities, it will mark a step in the right direction. Providing the school’s children with an opportunity to raise and sell grasscutters will give them a sense of responsibility and empowerment that will hopefully translate into other areas of their lives. If individuals within the community of Kpalimé witness that these children are able to successfully breed and sell grasscutters as a source of income, they might also be able to see that these children have the capability to be productive members of society and their perceptions regarding children with disabilities might change entirely. Furthermore, if the project is a success, it has the potential to expand to other schools for children with special needs across Togo and the rest of West Africa, serving as a vehicle to indirectly raise awareness for the inclusion of children with disabilities in the process.

The primary goal of Project Kpalimé is to empower children with special needs in West Africa, but it has the capacity to do much, much more. It has the capacity to raise awareness of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Kpalimé, Togo, but also West Africa, the United States, and around the world. A journey of 1,000 miles begins with a single step. Project Kpalimé is step 1.

VII. References

[i] Coe, S (2013). Outside the circle: A research initiative by Plan International into the rights of children with disabilities to education and protection in West Africa. Dakar: Plan West Africa. p 15, 20, 21, 24, 26.

[ii] WHO & World Bank (2011). World Report on Disability. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland.

[iii] "Volunteering in Togo." EXIS. N., 20 Aug. 2013. Web. 7 Dec. 2013. <http://www.exis.dk/en/volunteering-in-africa/togo.asp>.

[iv] Omeh, Darlington. "How to Start Grasscutter Farming in Nigeria and Ghana." Wealth Result. 6 Sept. 2013. Web. 1 Mar. 2013. <http://www.wealthresult.com/2013/09/Grassutter-Farming-Nigeria.html>.

[v] “Milestones.” Best Buddies International. 2014. Web. 10 Mar. 2014. <http://www.bestbuddies.org/best-buddies/milestones-without-timeline>.

Not ready to make a donation?

Support Grant